Blogs

‘Getting sick around here is a normal thing’: Precarity, exceptionality and governance in Nairobi’s ‘slums’ in 2020.

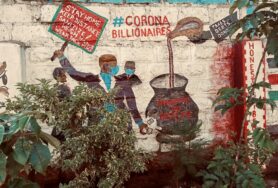

Painting in Nairobi, picture taken by authors

This is a guest blog by Mercy Gitonga & Joost Fontein (University of Johannesburg)

When, in late October 2020, we asked a ‘village elder’ in Mathare, one of Nairobi’s many ‘slums’, what effects Covid-19 was having in the area, he responded by saying ‘getting sick around here is a normal thing … but now if anybody dies it becomes corona’. He continued with an example of a man who had recently been stabbed to death nearby, but whose death had become attributed to the Covid-19 virus in local conversations. These statements echoed comments we frequently encountered in Mathare about the uncertainties, precarities and dangers – from disease, hunger and violence – that people living in Nairobi’s slums face every day. The skepticism carried by such statements also amounted to (and often complemented) sustained critique of the Kenyan government’s handling of the crisis. This critique particularly addressed the police coercion and violence that accompanied the ‘lockdown’ between March and June 2020, and the continuing curfews thereafter, as well as reports of the gross mis-appropriation of funds donated or allocated for medical supplies, face masks and humanitarian relief. As Kimari has discussed, the Kenyan government’s response has been typified by a ‘securitization of the pandemic’, from which police and high-level government officials are perceived to have benefitted exorbitantly to the cost of the common wanainchi (citizens). Such critiques emerged across all sectors of Kenyan society. However, just as the implementation of masking, social distancing and hand-sanitising regulations has been markedly different across the city – with adherence much more apparent in middle class areas like Kilimani and Kileleshwa than in the poorer eastern side of the city – so too has criticism of the government’s response been diverse. While in Mathare and other low-income areas critiques quickly focused on state neglect, violence and corruption, elsewhere they have tended to focus more on the lackluster nature of the official response to the pandemic, which many perceived as simply an attempt to mimic global lockdowns being enforced elsewhere.

As reports of increasing infection rates in schools dominated Kenyan news later in the year, amid reports of second waves and renewed lockdowns elsewhere, rumors were circulating that the Kenyan government was inflating infection rates in order to access funds from the World Bank and other international donors. With elections pending in 2022, other rumors suggested that the government was inflating infection figures in order to halt a series of high-profile political rallies by the Vice-president William Ruto, who many perceived as challenging the incumbent President, Uhuru Kenyatta. Conversely, as the government and media devoted more energy and print-space to publicity campaigns promoting the so-called BBI (Building Bridges Initiative) – widely understood as a deal between the President and the opposition leader Raila Odinga – references to these politicians as ‘super-spreaders’ and ‘Covid billionaires’ became increasingly common across social media. Yet as with the everyday risk of disease, hunger and violence faced by residents of Nairobi’s ‘slums’, such accounts of high-level corruption and political intrigue too are common discussion topics among Nairobians, which long pre-date the exceptional circumstances of the 2020 pandemic.

Refusing to exceptionalise Covid-19

In diverse ways across the globe, the Covid-19 pandemic has provoked a multiplicity of uncertainties that are related not only to questions of medicine and health care, but also economics, politics and social relations. These are intertwined with the uncertainties of the virus itself, its provenance, spread, and emergent strains, not to mention the veracity of official infection, recovery and mortality rates, or the efficacy of untested cures, tests and new vaccines. Across Nairobi the pandemic has provoked particular experiences of such uncertainties. Sometimes anxiety about the pandemic has seemed inversely related to the perceived ability of particular socio-economic groups to endure the effects of the virus, exactly because the adverse effects of the curfew and other restrictions are more immediate concerns. So poorer communities who may (or not?) be more vulnerable to infection, often appear less likely to adhere to preventative measures than wealthier communities already in a better position to mitigate the pandemic’s affects. For many people in and around Mathare, where a lack of formal employment and the need to ‘hustle’ informal livelihoods envelopes nearly everyone, Covid-19 restrictions have had profound effects on daily cash flow and weekly incomes (Nyadera & Onditi 2020), and thereby, in turn, on food security and health, as well as related problems of rising crime, teenage pregnancies and violence, particularly among youth.

Yet, as the village elder’s statements above suggest, for many such precarities and the difficulties of prioritizing extremely limited resources, were already familiar everyday experiences. The skepticism in the village elder’s statements, and those of many others, does not necessarily reflect a denial of the existence or efficacy of the virus, nor a lack of anxiety about infection; rather it stresses that there is little that is unusual about these quotidian uncertainties for residents of Nairobi’s informal settlements. And this attitude is reflected, perhaps, exactly in the lackadaisical use of face masks and hand-sanitizers across lower-income areas of the city, alongside common (sometimes gleeful) comments that ‘for once’ here is a disease that only affects white or rich people, or countries in the global north. For many in Nairobi’s neglected slums, everyday experiences of exceptional precarity, or perhaps of exceptionality as precarity (or vice-versa), means that there has often been deep reticence about exceptionalising the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic for fear that doing so would obscure the enduring structural inequalities and everyday depravations already common in these areas. As one community activist put it, ‘people in Mathare experience all manners of death which therefore does not make Covid death exceptional’. This is particularly the case in areas like Mathare where everything about quotidian life is already understood as exceptional to what is the aspired to, promised, or assumed norm. In this sense, not wearing a mask, or mocking those who do, is not just ‘ignorance’, nor fateful resignation, but may be a more determined kind of belligerence. Where masks are worn it often reflects reluctant compliance to avoid police attention, fines and demands for cash. Such unwillingness to ‘exceptionalise’ the dangers of Covid-19 may be about refusing to obscure the everyday precarities of slum life in Nairobi.

Potentialities and opportunities of Covid-19

But the everyday experiences of extreme poverty, hand-to-mouth living, violence, precarity and uncertainty that are common in places like Mathare, are not only about long-term neglect by city authorities. Such experiences, like all uncertainties, are also productive and full of potentiality/opportunity, whether for good or for ill. This is something that residents of Mathare and other ‘slums’ in Nairobi, like Kibera, have long engaged with; and is reflected in the plethora of community groups, local NGOs and other small organisations that constantly emerge, offering not only relief and aid in many forms, but also employment opportunities, something to do, or another ‘side-hustle’ in local parlance; an alternative to unemployment, hawking, gang life, drug use, or selling chan’gaa (illegal alcohol). In a context where the Covid-related closure of schools, diminished income opportunities and rising domestic debt has amplified local concerns about, for example, street muggings, teenage pregnancies and young people engaging in various forms of exploitative, transactional sex, participation in external or local community initiatives can offer attractive alternatives for kitu kidogo (‘something small’, i.e. money) and to relieve youth boredom. What we describe as the quotidian exceptionalities and uncertainties of everyday life in Mathare have long been recognized by many for the opportunities they can offer; not only for additional income and expanded social networks, but also new avenues towards morally-acceptable occupations, and the espoused ‘respectability’ and status that can accompany roles like ‘community volunteers’, ‘advocates’, ‘activists’, ‘social workers’, and ‘health promoters’.

And in this sense Covid-19 has again brought no exception. Many, if not all of Mathare’s existing local organisations, self-help and community groups, as well as external organisations working in the area, have been busy running Covid-awareness campaigns, public seminars, workshops and training sessions, as well as offering guidance and counselling, medical referral/response services, and distributing food or small financial allowances where and when available. Organisations ranging from MSF, Red Cross and USAID to local outfits like SHOFCO (Shining Hope For Communities), Ghetto Foundation, Generation Changers and Mathare Youth Sports Association (MYSA), to name only some, have been handing out face masks, hand sanitizers and setting up hand-wash stations; rendering such Covid-related services on the back of existing vaccination, healthcare, sexual and mental-health awareness campaigns. Not only has Covid-19 given additional purpose for such organisations – albeit without changing the parameters by which they govern themselves, or their position within wider structures of governance across Mathare and the city – it has also created new opportunities for members of the community to access the ‘small benefits’ that can accrue from such activities. And for some the potential opportunities that Covid -19 has brought are not so small. The Billian Foundation, for example, headed by Billian Okoth Ojiwa, a vocal social justice activist, KANU Party Youth Chairman, and founder of the Ficha Uchi Initiative which supplies uniforms and sanitary towels for school girls, as well as an aspiring Member of Parliament, has managed to marshal Mastercard funding for Covid-related activities, which many perceive as part of his forthcoming parliamentary campaign.

An unexceptional part of exceptional world events

The opportunities that the Covid-19 pandemic has brought for some in Mathare, may not in any way equate with those requisitioned by Kenya’s so-called ‘Covid billionaires’, but they are significant. This is not merely about accessing kitu kidogo, respectability, something to do, or even support for local political campaigns. For those marshalling donor funds on behalf of local community groups and NGOs, or busy attending Covid-19 awareness-raising workshops, the pandemic has also offered an opportunity to take part in a world-wide, global event, to place their lives not as exceptional to those of people elsewhere in the city, the region and the world, but in close continuum with them; much like what Das (2011) has described among slum dwellers in Delhi, India. Like the examples that Ferguson (2002) cites in his seminal discussion of a letter found on two young men from Guinea discovered dead in the landing gear of an airplane that landed in Brussels in 1998, this is neither resistance nor compliance: ‘neither a mocking parody nor a pathetically colonized aping but a haunting claim for equal rights of membership in a spectacularly unequal global society’ (2002: 565). Or as Monica Wilson identified for ballroom-dancing Africans in colonial Northern Rhodesia in the 1930s, a way of ‘pressing, by their conduct, claims to the political and social rights of full membership in a wider society’ (Ferguson 2002: 555). While the flaccid claims of some international commentators in early 2020, that the Covid-19 pandemic might be a social leveler because of its global nature – ‘that we are all in the same boat’ – are simply not true, as the everyday struggles faced in Nairobi ‘slums’ make plain, this does not diminish the aspiration that it could be so, at least for some of Mathare’s residents.

Therefore, even as many in Mathare express a deep reticence about exceptionalising the risks of the Covid-19 virus in their defiance of perceived attempts to obscure the structural inequalities and quotidian deprivations they already face, for others Covid-19 has also provided an opportunity to be a ‘unexceptional’ part of exceptional world events. A conversation with one of Mathare’s ‘community health promoters’ captured some of the conundrums that this can raise:

Despite the rumours that Covid does not exist, D. believes that Covid does exist, he believes that in China, Italy and USA people are dying. Therefore, as an individual he makes it is his responsibility to wear a mask, maintain distance and sanitize … However his adherence to masks and hygiene does not come without a price, as he is often mocked as an easy believer who believes everything at face value … [or] people ridicule him for pretending to be special, or better than others. Some claim that he is in cohort with the government … justifying fake numbers and spreading Covid propaganda so that it can get money from the World Bank, WHO and other donors. However, this does not deter him, as he is a community activist with both Ghetto foundation, and Billian Foundation, and he believes it is his responsibility to educate his community on Covid regardless of whether they believe it or not. (Fieldnotes 16/11/20)

This reflects a profound ambivalence that Covid-19 has created for many people in Mathare: between, on the one hand, refusing to hide their exceptional everyday abjection under the cloak of a world pandemic, and on the other, being a willing but ‘unexceptional’ participant in those global events. It also reflects the contradicting critiques that the Kenyan Government has faced: that its response to the crisis has been marked either by an excess of ‘governance’, or a distinct lack of it; that it was either a too heavy-handed and too corrupt – a disproportionate and cynical interruption into everyday lives – or a lackluster ‘imitation’ of restrictions hastily introduced everywhere, but enacted here merely in the interests of demonstrating Kenya’s place in a global order of governments and nations.