Blogs

Stay at home? Essential non-compliance with the State of Emergency in the urban margins of Maputo.

Photograph taken at Av. Milagre Mabote, neighborhood of Maxaquene of an informal vending stall selling beer, among other things. Covid-19 regulations prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages in public spaces, this rule is ignored in many places. (Photograph made by Salamão Nicasse).

Tirso H. Sitoe and Nikkie Wiegink*

My son, I have nothing to eat. We are told at some point to stay home. Here, I’m at home and doing my small business to pay the bills here at my house. My children need to eat. We all need to eat. They who say to stay home, have something to eat. Here, my children usually sell. I am a maid in the city. But my boss told me I was supposed to stay home because of COVID-19 and how am I going to pay the bills here at home? I still haven’t seen this disease that they say exists, killing people here. Here in Maxaquene, more people die of HIV-AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria or cholera. But also, those who buy things here at my stall, are neighbors. They are people who do not have the money to buy things in Nigerian establishments all the time. Things are very expensive there. The salary ends there and there is nothing left. So, people can come here without wearing masks, to buy. You can come here without washing your hands to buy. We have water problems. Where are we going to get this soap and water? Neither the municipal police, nor the head of the block or the neighborhood secretary rule here. If they also have stalls like mine in front of their house? Each person eats where they are, right? (This quote is from an interview conducted in the Maxaquene neighborhood, on 18/09/2020.)

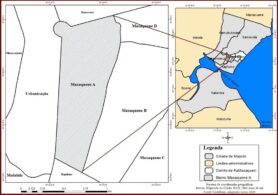

These are the words of Teresa, a woman living in Maxaquene A, which is one of the peripheral neighborhoods of the city of Maputo and is also known as one of the city’s slums in addition to Mafalala (see Figure 1). Teresa’s story exemplifies the trajectory of many residents of Maxaquene, who due to Covid-19 measurements lost their jobs in “the city”, the richer, central areas of Maputo. To make ends meet Teresa resorted to informal vending. She was selling essential products such as tomatoes, onions, potatoes, and cooking oil in the front of her home. This type of informal commerce, highly visible along the main roads of the neighborhood (see Figure 1), is the economic base of many families residing in Maxaquene. Most of this activity is carried out by women (some as heads of families) and children.

Figure 1. Map of Kamaxaquene Municipal District, elaborated by the research group.

In view of the worsening and exponential increase in contamination by Covid-19, the Government of Mozambique adopted in March 2020 through Presidential Decree No. 11/2020 the “State of Emergency”, throughout the national territory, in order to reduce the contamination risks and prevent a collapse of the already fragile national health system. The government initially tried to close down informal markets, but soon recognized their fundamental role in economic activities. Nevertheless, as Covid-19 has caused sudden income loss for enterprises and households, and the National Institute of Statistics reported that about 120,000 jobs were lost. As domestic demand fell and mobility was largely halted, much of the demand for non-formal trading and services in Maputo also declined.

The excerpt from the interview with Teresa, illustrates how Covid-19 made visible the further marginalization of people living in contexts of constant precariousness. As the February 2021 report of the World Bank noted, the urban population has been hit hard by Covid-19. Loss of earnings and employment have particularly affected the urban households depending on work in the non-formal sector, the World Bank concludes. The report notes that over 50% of urban households are running out of food.

A fundamental component in the government’s message was to “stay at home.” People were only allowed to go out on the street in fulfillment of basic needs. However, as the words of Teresa suggest, the rule to stay at home and some of the other regulations such as wearing a face mask and washing your hands are regularly not followed. In Maxaquene “you can buy without a mask”, which reveals a shared experience of essential non-compliance with the measures presented by the State of Emergency. This is not necessary a form of contestation of state regulation, but rather reveals the distances between policies and the reality lived by residents of the Maxaquene neighborhood. The daily practices of street vendors like Teresa, reflect the modus vivendi of most residents of the Maxaquene neighborhood, which is characterized by a kind of everyday non-compliance with the Covid-19 regulations to continue to survive.

Teresa says that “neither the municipal police, nor the head of the block or the neighborhood secretary rule here. If they also have stalls like mine in front of their house? Each person eats where they are, right?” This statement is interesting, as in fact these practices of non-compliance do not unfold in a context devoid of rules or control. Teresa acknowledges the presence of the “head of the block” (in Portuguese, chefe de quarteirão) and the “neighborhood secretary”, the main authorities at the neighborhood level. These actors are part of a tight system of control that is very much intertwined with the governing party Frelimo. The chefe de quarteirão is however not a formal government position and these local authorities have no legal abilities to enforce the law. Rather the main role of these authorities is to report to other authoritative actors higher in the hierarchy. This way, they serve as the eyes and ears of the government (and by extent the Frelimo party) at the local level. During past calamities, such as floods, these local authoritative actors have contributed to the implementation of successful emergency measures, such as the mapping of affected families and have facilitated the reporting to the National Institute for Disaster Management (INGC) (Mazzolini et al 2020: 4).

The chefe de quarteirão and the neighborhood secretary have also been identified as central actors in the implementation of measures to mitigate the Covid-19 pandemic. But in practice, as Teresa’s words illustrate these actors tolerate or condone certain practices clearly in defiance with the Covid-19 regulations. More so, as Teresa notes, these regulations are also breached by these very local authorities. She explains this by referring to the absence of “rule.” But we could also see this as a kind of complicity that involves the local authorities and the residents. Authorities such as the chefe de quarteirão depend for their power on the support of the residents. This support could easily wane in the face of harsh measures that affect already vulnerable residents of Maxaquene. At the same time, these authorities have also increasingly relied on informal vending to make ends meet, as their fellow residents.

For Teresa the shared practice of non-compliance makes complete sense. The remark: “each person eats where they are” refers loosely to a popular phrase in Mozambique, “o cabrito come aonde está amarrado”, “the goat eats where it is tethered”, which refers to corruption, mainly of the state officials. However, it may gain a different ring in the context of the Covid-19 measures. In this context, it legitimizes people’s activities to get by in trying circumstances, while breaching the regulations of the State of Emergency.

*The research in Maputo was conducted by Tirso Sitoe and Salamão Nicasse